Passive bioacoustics in pacific northwest forests

General information and data collection

|

The northern spotted owl demography monitoring program has been highly effective to understand population change, but demographic studies take a great amount of effort and sustained funding, and because of precipitous population declines, few individuals occupy and reproduce in historic territories. We have been testing an alternative method to monitor trends in spotted owl populations that takes advantage of technological advancements in non-invasive detection equipment and can be used to monitor many other species in addition to spotted owls. We are conducting passive acoustic monitoring using autonomous recording units (ARUs), which is a fast-growing area of wildlife research, especially for rare, cryptic species that vocalize but are difficult to detect otherwise.

Since 2017 we have surveyed over 1800 sites with ARUs and collected well over 500 terabytes of sound files representing over a million hours of recordings! |

Spotted owl and Barred owl detection probabilities

We used ARUs to detect calls of spotted and barred owls from March-July 2017, we recorded with ARUs each night at 30, 500-ha hexagons (150 ARU stations) with likely spotted owl activity in Oregon and Washington. Even in a study area with low population estimates (Washington’s Olympic Peninsula), conditional detection probabilities (i.e., when spotted owls were present) in hexagons exceeded 0.95 after 5 weeks of ARU deployment. In two Oregon study areas, detection probabilities for spotted and barred owls approached 1 within 2-3 weeks. Background noise from streams, rain, and wind negatively affected detection probability over all study areas. We also applied known demographic information about spotted owl pair locations to ARU detections, which revealed patterns in vocalization intensity that is helping to distinguish territorial vs non-territorial (“floater”) birds using only bioacoustic data. Barred owl use was lowest in hexagons with nesting spotted owls, but use approached 1 in hexagons where spotted owls were not detected by mark-recapture surveys. These results suggest that a passive, occupancy-based study design could be a promising method to monitor spotted owl populations.

See this paper for details:

Duchac, L. S., D. B. Lesmeister, K. M. Dugger, Z. J. Ruff, and R. J. Davis. 2020. Passive acoustic monitoring effectively detects northern spotted owls and barred owls over a range of forest conditions. The Condor 122:1–22. doi: 10.1093/condor/duaa017/5825670

See this paper for details:

Duchac, L. S., D. B. Lesmeister, K. M. Dugger, Z. J. Ruff, and R. J. Davis. 2020. Passive acoustic monitoring effectively detects northern spotted owls and barred owls over a range of forest conditions. The Condor 122:1–22. doi: 10.1093/condor/duaa017/5825670

Owl community use of a post-fire landscape

Owls are important avian predators in forested systems, but little is known about landscape use by most forest-adapted owl species in environments impacted by mixed-severity wildfire. To better understand how owls use post-wildfire landscapes we leveraged advancements in passive acoustic monitoring using autonomous recording units. The technology has proven effective for multi-species surveys, especially if some species are rare, nocturnal, or otherwise difficult to detect by traditional means. In 2017 we surveyed the interior and adjacent unburned areas of a 10,700 ha mixed-severity wildfire that burned in 2015 in southwest Oregon. Our objectives were to identify patterns of landscape use by five species of forest owls: barred owls (Strix varia), great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), western screech-owls (Megascops kennicottii), northern pygmy-owls (Glaucidium californicum), and northern saw-whet owls (Aegolius acadicus). We also aimed to quantify post-fire landscape use by northern spotted owls (Strix occidentalis caurina) but they were too rare on the landscape to conduct similar analyses as with the other species. Our occupancy modeling results showed a strong positive relationship between fire severity and probability of use by western screech-owls and a similar, but somewhat weaker relationship for northern pygmy-owls. Northern saw-whet owls were only detected very near the fire’s perimeter or outside the burned area altogether. Barred owl use decreased with increased fire severity, and we observed generally low detection probabilities for great horned owls, but use was highest in unburned or low-severity areas. In all, four out of the five species appeared to use recently burned forests at different levels, with only northern saw-whet owls avoiding the burned area completely. These previously undocumented patterns could provide insights to managers and policymakers in the Pacific Northwest as climate shifts, and fires may increase in size and severity.

Published paper coming soon!

Published paper coming soon!

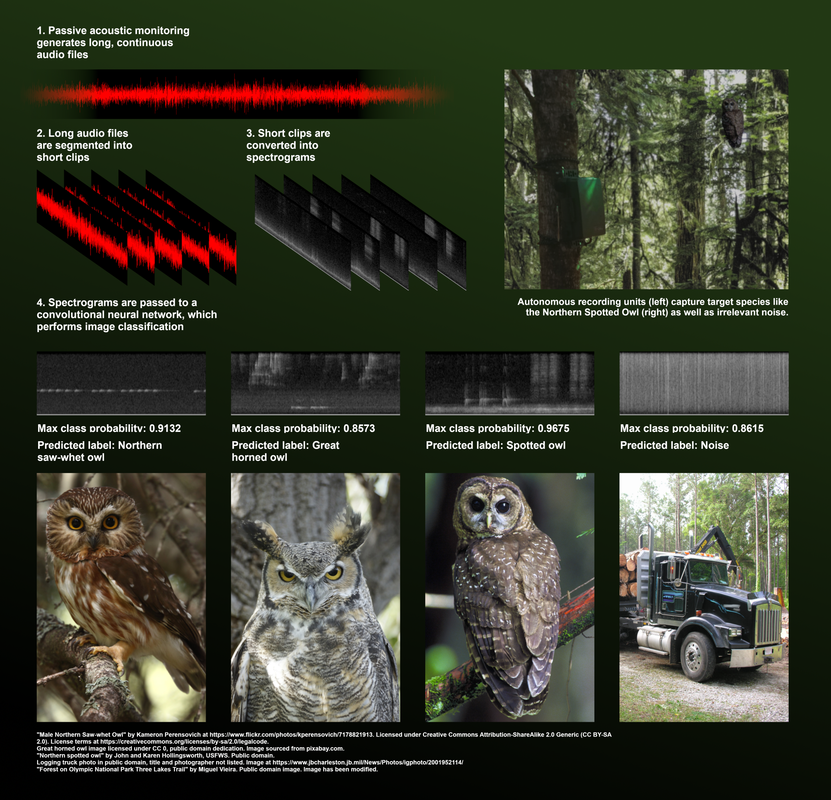

Convolutional neural network

|

Passive bioacoustic monitoring shows great promise, but we are challenged with locating and identifying target species vocalizations within large volumes of audio data. To address this issue, we have partnered with computer scientists at Oregon State University to develop a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) that effectively automates the detection of vocal activity of several target species, including spotted owls. Currently our CNN works for 6 owl species profiled below. Our initial results are highly promising, with the CNN performing as well or better than human reviewers in detecting spotted owl calls from large volumes of data. We are further developing the CNN at a large scale and expanding our target species list to include non-owl birds as well as several mammalian species.

See these papers for more details: Ruff, Z. J., D. B. Lesmeister, L. S. Duchac, B. K. Padmaraju, and C. M. Sullivan. 2020. Automatic identification of avian vocalizations with deep convolutional neural networks. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 6(1):79-92. doi: 10.1002/rse2.125 |

OWL species profiles

Northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina)

|

The northern spotted owl was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1990. Major threats to spotted owls are timber harvest, wildfire, and barred owls. Providing adequate amounts of suitable forest cover to sustain the subspecies is a major component of the recovery plans and a driver in the basic reserve design and old forest restoration under the Northwest Forest Plan. Spotted owls use vocalization to establish and defend territories, find mates, and for communication between pairs. The typical territorial call is a stereotypic 4-note hoot. Other common calls are an ascending “series location” call and a contact “whistle” to communicate between pairs, and pair duets.

|

Barred owl (Strix varia)

|

Barred owls are a congener to spotted owls that have expanded their range from eastern North America over the past 50 years to now encompass the entire range of the northern spotted owl. Barred owls are a slightly larger, more aggressive species, with more generalized diet and habitat requirements, and higher fecundity and survival compared to spotted owls. Barred owls use the distinctive 8-note hoot to establish and defend territories, find mates, and for communication between pairs. Other calls include wails and "caterwauling" duets between pairs.

|

Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus)

|

Great horned owls are large, powerful owls with the most widespread distribution of any owl species in North America. They occupy a wide range of forested habitats usually adjacent to wetlands, agricultural fields, meadows, or clear-cuts, as well as desert, grassland, and suburban areas. In the Pacific Northwest, great horned owls appear to avoid forest patches containing over 70% contiguous old growth. These owls are considered a primary predator of adult northern spotted owls. Great horned owls are diet generalists and opportunists, but their primary prey species are small mammals, mainly lagomorphs and rodents. Other prey include birds, insects, bats, and herpetofauna when available. Great horned owls have a deep, soft 4-note hoot, along with various squawks and grunts mainly given by females.

|

Western screech-owl (Megascops kennicottii)

|

Western screech-owls are habitat generalists and will use a wide range of vegetation types as long as a cavities are available for nesting. Western screech-owls are slightly larger than both northern pygmy and northern saw-whet owls and take mainly mammalian prey. Recently, research has shown evidence of population declines in the Pacific Northwest, especially in British Columbia, presumably due to barred owl predation and competition. Typical sounds include a “bouncing ball” call that begins slowly and speeds up toward its end, and a double trill used to communicate between pairs. Females also produce a descending whinny call, likely to solicit feeding and copulation.

|

Northern saw-whet owl (Aegolius acadicus)

|

Northern saw-whet owls are small owls with wide distribution across North America. In the west, they typically nest in dense coniferous forests, but roost and forage in deciduous patches in riparian areas, openings, and edges. Northern saw-whet owls primarily hunt mice and other small rodents. They are opportunistic foragers and unlike some other owl species, which show strong site fidelity, they may be nomadic, selecting new breeding locations based on prey abundance. Both male and female northern saw-whet owls produce rapidly repeated single-note hoots as their song, sometimes continued over an extended period. Other calls include wails, whistles, and a sharp descending “skew” bark.

|

Northern pygmy-owl (Glaucidium gnoma)

|

The northern pygmy-owl, the smallest owl in the Pacific Northwest, is more diurnally active than any other species in this study. In its range, restricted to western North America, it is thought to use a variety of forest ages and types for breeding habitat, likely in part due to its generalist diet consisting of birds, small mammals, and insects. Though they can be quite common in parts of their range, there is limited information about this species as they are infrequently studied. The typical northern pygmy-owl song is a high, repeated hoot every 1-2 seconds, sometimes continued for several hours. At times, they begin vocalizing with a rapid trill before a series of typical hoots.

|

Species of interest

Marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus)